ecuador's mysterious out-of-place cloud forests

it's kinda like area x from annihilation but without all the bad stuff that happened to the characters

an anomaly has clouded the andean foothills above ecuador’s most populous province. natural forces have conspired to birth a lush tropical forest that’s both familiar and completely out of place. some of ecuador’s iconic birds have taken up residence here, in habitat that’s both perfectly suited for them and totally wrong.

ok, maybe i’m dramatizing things a little bit. but there’s no doubt that the little patch of forest along the road leading north out of cumanda, ecuador, feels a bit like annihilation’s area x. i couldn’t find the forest’s name, but ebird refers to it as “esperanza alta” after one of its waterfalls. i’d found it while looking online for a place near guayaquil to see cock-of-the-rocks, the quirky icons of the andean cloud forest, and coordinated with a local birder named jaime to explore the spot. but after spending the morning there, i realized: our field guides said there should not be cock-of-the-rocks this close to guayaquil. and many of the birds along the road did not belong at that elevation.

i’ve been wondering since the trip ended what was going on with the spot. and i’m happy to report that, while researching last week’s post, i stumbled across the answer.

gabriel and i sensed that things would be weird when we arrived at our nearby hotel the night before. the brand-new, fluorescent-lit, six-story tower was surrounded by ten-foot, razor wire-topped walls, and was the only building on a scrub-covered plateau overlooking the humble town of cumanda. it had a fancy restaurant, a rooftop pool, and everyone on the staff had matching neck tattoos (but they were really nice and had a boxed breakfast waiting for us at 5am the next morning!). not that this had anything to do with bird habitat. just silly.

anyway, we picked up jaime in downtown cumanda and drove 20 minutes from the tropical lowlands into the andean foothills, pulled over, and… we were there. my previous understanding was that seeing andean cock-of-the-rocks requires a strenuous hike into a remote ravine. but these birds had chosen a spot next to a road popular with local tourists for its many waterfalls. we needed only to take a few steps into the woods to witness the show. beginning at first light, three, plump, fiery-red birds hopped back and forth on moss-covered branches with their necks outstretched, emitting raucuous squeals hoping that a female would show up. no females came after a half hour, so the cock-of-the-rocks dispersed and jaime and i went birding.

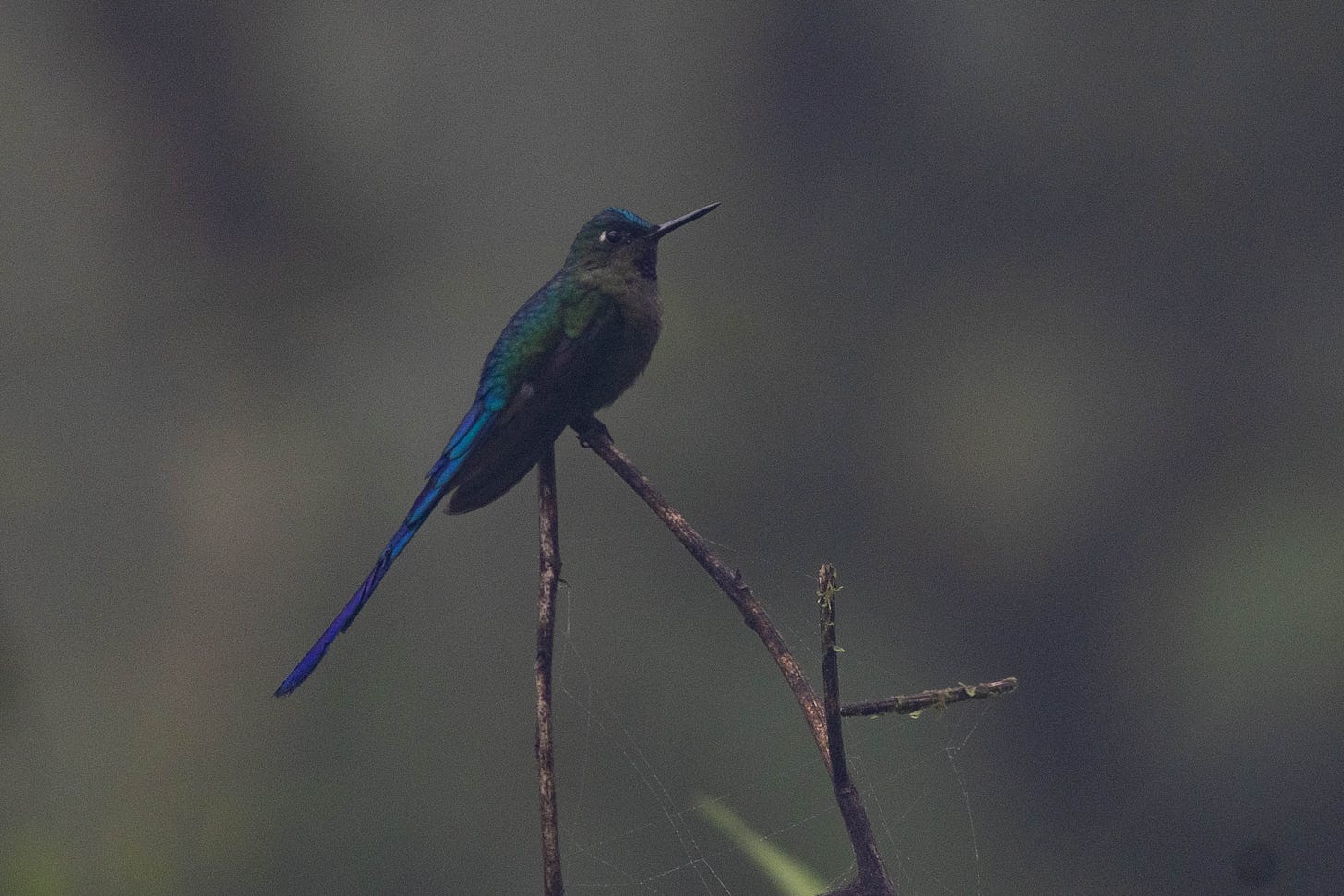

but the roadside cock-of-the-rocks were just the start. the citizen science/bird tracking app, ebird, flags and makes you add documentation to out-of-place birds. it flagged nine of the 69 birds we saw that morning, versus the zero flags you’d expect. there was a pattern to the alerts. sickle-winged guan, fawn-breasted brilliant, smoky-brown woodpecker, and rufous-collared sparrow are all higher-elevation birds in ecuador, usually inhabiting forest above 3300 feet and often above 6600 feet, versus the spot we were birding, which averaged around 2500 feet.

jaime, gabriel, and i, and later our guide roberto, all speculated about the cause. perhaps nearby volcanoes and the local topography forced colder air into the region, creating a cloud forest microclimate. the hills sat at the southernmost edge of a spur of the andes; perhaps birds were getting funneled there, like migratory birds get funneled into peninsulas. but i found the answer last week while researching the habitats of western ecaudor, in a botany paper published by botanists lars peter kvist, laurence skog, john clark, and richard dunn.

so, i explained last week that the andes isolate western ecuador’s lowlands. the northern part of those lowlands is one of the wettest places in the world, and the southern bit is dry, nearly desert in some places. kvist wrote that between those areas, local topography can have a big impact on what kinds of forests develop. for example, low coastal ranges and andean foothills arising from moist, tropical lowlands force warm and wet pacific air upward, shrouding the hills in near-constant cloud cover. this, in turn, creates lower-elevation layers of isolated cloud forest from 1600 to 3000 feet. the traditional cloud forest then begins in earnest at around 6000 feet in the andes (this is variable, of course).

the botanists were interested in these isolated forests for a different reason than i: isolation causes endemism, or species unique to a certain place. they were studying a family of colorful tropical plants called gesneriaceae, and wrote that 210 species from this family are found in ecuador, 107 are native to western ecuador below 3300 feet, and 23 of those 107 species are endemic to isolated low-elevation cloud forests like the one gabriel, jaime, and i were birding. and, as is the case across western ecuador, these plants and the low-elevation cloud forests they inhabit are threatened by widespread deforestation from agricultural interests.

the esperanza alta forest is special to jaime; he’s seen more birds there than almost anyone, and he charges money to show it to birders hoping to see cock-of-the-rocks while visiting guayaquil. whenever he brings a group there, he gives money to the impoverished family that owns the property; he hopes that the money will keep them from replacing the forest with banana plantations. because if they clear it, there’ll no longer be a known cock-of-the-rock spot within reasonable driving distance of guayaquil. gabriel and i joked about buying the property and converting it into a reserve and ecolodge—we saw more bird species in four hours along that road than at any other single spot during our trip. we don’t have enough money to do that, though.

after reading more about these foothill cloud forests, i don’t think “weird” is the right way to think about them. of course nature doesn’t have strict elevational boundaries—cloud forests will grow where the conditions are right, and lots of factors could make conditions right. and of course there are cloud forest birds in those forests. elevation is just a number, and birds are generally better botanists than they are mathematicians (with notable exceptions). while researching this post, i noticed that some field guide accounts of certain cloud forest birds specifically call out that they’re seen at lower elevations in western ecuador.

rather, esperanza alta is emblematic of the complexity of tropical ecology—the unique microclimates and microhabitats that can form and create endemism. it also represents the threat that unprotected and understudied tropical habitats face. at any moment, this unique spot could fall prey to deforestation. and there are surely other places like it, understudied or underappreciated patches of habitat with no protections whose endemic life would go extinct without fanfare should the habitat be cleared.

postscript

mark your calendars: i’ll be doing a virtual intro-to-birding for wave hill in the bronx on thursday, april 6 from 4pm to 5:30pm. register here.

i think i’ve more-or-less exhausted myself of ecuador content, so i’ll be going back to nycposting and my regular publication schedule of ~2x/month. here’s a barred fruiteater saying “aaaaaaaaah!!!!!!!!”