i mean if i find a cool bird i'm going to tell you about it

this ones called a cave swallow

finding out-of-place birds is usually a matter of luck, and it’s certainly not something you expect to happen on any given day out birdwatching. but in some very specific instances, you can predict, or even expect, certain vagrant birds to show up in certain places.

that’s the case of the cave swallow, a bird whose northernmost breeding range is texas and who mainly lives in the caribbean and central america. starting only in the past three decades, cave swallows have appeared annually across the northeastern united states when the right weather patterns happen at the right time of year. there’s still some mystery behind these vagrants, but their predictable behavior makes them an almost-expected occurrence in nyc in some years.

those weather patterns happened earlier this month, and it led to my own brooklyn cave swallow encounter. please forgive me if this post is too self-congratulatory for you but what else is a newsletter if not an exercise in self-indulgence?

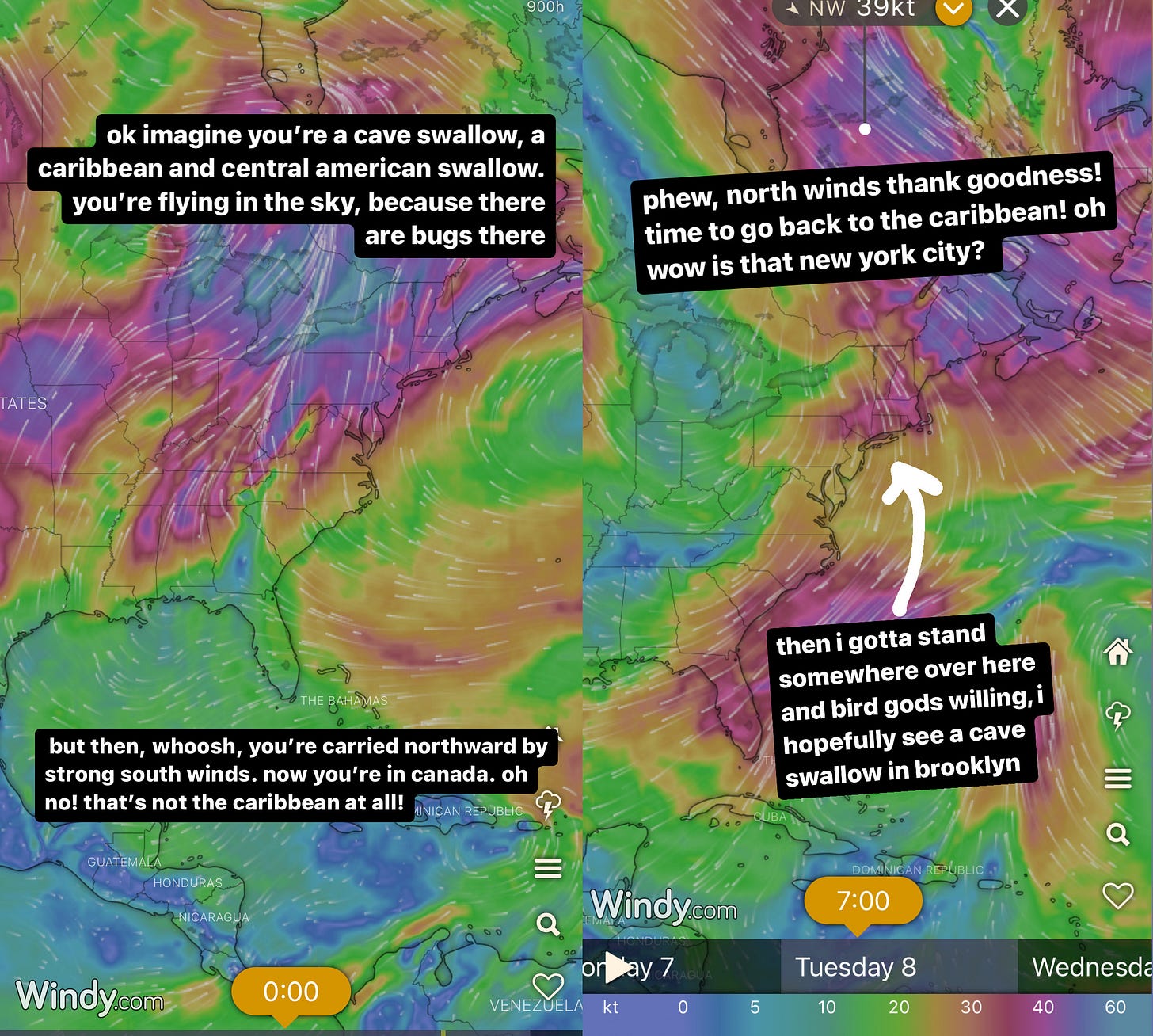

it started on friday, november 4, when the temperature started rising across the northeastern us. the app i use to track the winds showed that a few hundred meters off the ground, there were strong (40+ knot) winds blowing all the way from texas and the caribbean northward. by saturday, cave swallows started appearing on the great lakes and even as far north as lake champlain. on sunday, i looked at the forecast: the winds would shift west on monday and then northwest on tuesday. this exact weather pattern occurring in november— strong south winds followed by northwest winds — is well-known among northeast birders as cave swallow weather. the logic goes that the strong winds push migrating cave swallows north, then northwest winds force them to the coast, which they follow back west and south.

on sunday, i posted on instagram that i planned to see a cave swallow on the following tuesday. and on tuesday morning, despite having only one free hour after the 6:30 dawn for the attempt, i headed to coney island to try my hand at finding one. i got there at 5:45 to see the lunar eclipse, perched up on the pier with my camera, watched the sunrise, and waited. big flocks of blackbirds and goldfinches started appearing on the horizon and flying westward, and after only twenty minutes, a fluttering bird diverged from a larger flock and headed right toward me along the beach. it was clear that this bird was a swallow based on its distinct shape and flight style. as it came closer, i saw a short, squared-off tail, pale orange throat, rusty orange rump, and dark forehead—the field marks that separate cave swallows from any of new york’s breeding swallows.

ok, so now that i’ve done my bragging, let’s talk about the strange emergent phenomenon of cave swallows visiting the northeastern united states. cave swallows only started appearing in the united states in 1910, where they were rare breeders in texas. but then, in the 1960s, their population started exploding alongside human development as they started nesting in places like highway overpasses. sometimes they even displaced more common swallows like barn and cliff swallows. these new birds would migrate south each winter, beginning in the mid-autumn. similar population growth was occurring in the carribbean, and those cave swallows started nesting in south florida in 1987. today, the furthest northern extent of their breeding range is still texas and florida.

then in spring of 1990, new york and new jersey recorded their first-ever cave swallows (new york’s was found in part by kenn kaufman at the jamaica bay wildlife refuge in queens). more records came in the following years, consisting of mostly juvenile birds in the autumn. those records increased in frequency until today, where the birds are expected visitors in the northeast, appearing every few years in new york state and annually in new jersey, especially around cape may. november cave swallow appearances are so expected in new jersey that the bird is no longer included on the state’s “review list.” that means the state’s ornithological society doesn’t consider the bird’s presence to be notable enough to warrant their expert review.

it’s not totally clear where the northeast cave swallows are coming from. three birds that were analyzed as part of a 2011 study all matched the texas population, while there’s evidence to suggest that spring cave swallow records on the atlantic coast come from the caribbean birds. it’s difficult to tell the texas birds from the caribbean birds by sight alone, regardless.

ultimately, it’s clear that the increase in northeastern records correlates with ongoing range expansion. it’s also clear that new york city is a good place to see them given its coastal migratory bird hotspot status. i hope you take this knowledge and use it to see cave swallows yourself. or like, show cave swallows to your friends as a fun little party trick. a party trick that requires very specific weather patterns and timing and luck or whatever.

postscript

going back to a weekly posting schedule for a little bit, just because i wanted to get this post out before the end of the month and the next post has a slightly time-sensitive thing in it.

the winter is closing in, but the birds aren’t gone yet. lots of us birders consider late october into november to be “rarity season,” since it’s when young birds attempting to migrate for the first time get turned around and show up places they’re not supposed to be. we call them vagrants.

people sometimes ask what happens to the vagrant birds. do they always die, or do the cave swallows find their way home? lots of them probably die pretty quickly due to the lack of proper food or habitat. but not all of them. if there are a lot of vagrants of a specific species to one place, they might establish a new population. this has happened lots of times on islands—vagrant finches in hawaii ended up evolving into dozens of new species, for example. some vagrants might persist alone in their new home for a long time, like morris the gannet, an atlantic ocean bird who’s been living off the san francisco coast for a decade. others might continue migrating to and from their new spot, like the western tanager who came back to a small manhattan park for three winters in a row. and maybe some of them make it back home—the tropical kingbird i spoke about last month was seen 150 miles south a few days later, perhaps on a journey back to the tropics.

here’s another vagrant i saw recently: a townsend’s warbler that doug gochfeld found in fort greene park last week. this bird usually lives on the west coast, and i went to go see it this past weekend because i like cute little tweety birds and i saw people were getting nice photos of it. the bird has drawn quite a crowd already, and seems to be doing alright despite the cold weather.