let me tell you about the hat i got on vacation

it has a cardinal on it

southeastern arizona hosts birds you can’t see anywhere else in the united states. when i visited a gift shop at a lodge there, i could have gotten one of several different caps featuring those unique birds. but instead, i got the hat displaying a bird i could see in my brooklyn backyard, the northern cardinal.

northern cardinals rank among the northeast’s most common native birds, but their presence in arizona tells the complex story of evolution; they might not be northern cardinals at all, but a cryptic species all their own. the fact that arizona’s cardinals could be hiding this secret has lived in the deep recesses of my mind since i wrote about it for gizmodo a few years ago, based on research led by ohio state postdoc kaiya provost. i was eager to observe and photograph the cardinals i saw in arizona last week to see if they looked any different from the cardinals back home in brooklyn, like this one:

i still think species is kind of a made-up concept, but there’s no doubt that a variety of factors spanning eons can cause two groups of organisms to start isolating and evolving to the point that they won’t, or can’t reproduce with each other anymore. perhaps the most common factor is geographic isolation; if some barrier like a desert or a glacier or an ocean comes between two groups of the same species, they might become two different species. this is called allopatric speciation, for you nerds out there.

such a barrier once traced the north american continental divide, separating the sonoran desert (spanning from arizona to the south and west) from the chihuahan desert (from new mexico to the south and east), called the cochise filter barrier. it’s a ”filter barrier,” rather than just “barrier,” because it isolated some but not all of the creatures on either side of it. glacial cycles have caused these regions to at times connect as one big ecological region, and at times separate with patches of other kinds of habitat in between. they’re connected today.

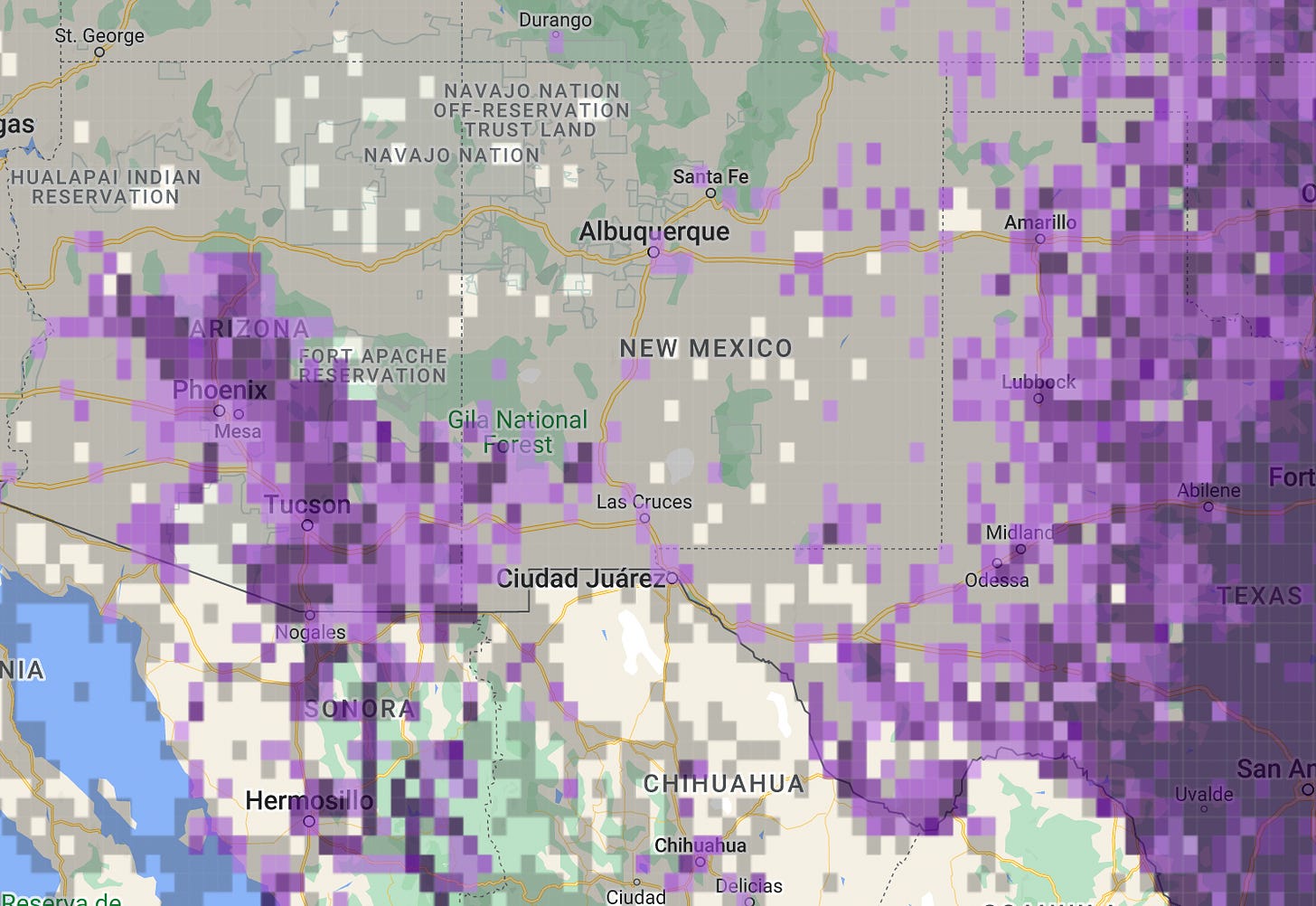

cardinals seem to have been split by this filter barrier. check out this map from the ebird database and you’ll see a clear split between two clusters of cardinal sightings, one in arizona/mexico and one in texas. cardinals can disperse widely and flock to bird feeders, so it makes sense that there will still be some cardinals in the middle. but the barrier’s former presence is apparent in the map, even if it’s not apparent when you’re driving around the area.

provost’s 2018 paper, the one i wrote about for gizmodo, asked about what was going on here, and whether the birds were really isolated in the evolutionary sense. had the filter barrier left a permanent imprint on their dna and separated them into two distinct populations? what was keeping them separated when the barrier wasn’t present?

in one experiment, they gathered song recordings from both the western (sonoran) and eastern (chihuahan) cardinals, and played them for each other. as expected, the territorial male cardinals got pissed off when they heard the songs from their local group. but when they heard the other group’s song, they didn’t pay any mind—as if they were the songs of a different species. then, the researchers did dna testing, demonstrating that there was almost no gene flow between the populations. birds from one desert weren’t reproducing with birds from the other, and haven’t mixed in a million years.

it seems like, at some point, a barrier separated these two cardinal populations. then, their songs started to differentiate, like language dialects. the barrier disappeared but the dialect differences remained, and the two populations became isolated—and may not recognize one another as the same species anymore, according to the paper. it will probably require more experiments to confirm that these birds actually meet the standard to qualify as different species—for example, the researchers mostly performed their experiments on male cardinals. however, a 2015 proposal has already suggested splitting northern cardinals into six species, with arizona’s northern cardinal becoming the western cardinal. (the aos turned that proposal down).

species status aside, these western cardinals were certainly different from my local cardinals. i can’t say the difference in song was immediately noticeable to my ear, but i did manage to get some up-close photos. at the very least, the southwestern birds’ beaks were comically large compared with the eastern birds, so big that the black face mask doesn’t connect across the forehead, with a noticeable downward curve to the upper beak, as described in birds of the world. the red seemed to have a slighly paler quality, too.

given all the mental energy i’ve spent on them, i was really excited when i saw arizona’s cardinals—more excited, even, than i was to see pyrrhuloxias, the northern cardinal’s sister species found only in the southwest. so when it came time to buy the hat i’d wear around to brag about my trip to arizona, it only made sense that i’d get the one with the cool story.

also cardinals are extremely good birds overall so i’m happy to always have one around on my head.

postscript:

i saw a lot of other cool birds—i wrote up a little trip report about the whole shindig, linked here. i might write newsletters about some of the other photos if i think of anything cool to say about them but in the mean time here’s a few of my favorites.