these butterflies have a head for a butt

a good old fashioned blog post

prescript

i have so much programming this fall, so if you’ve wanted to take one of my walks but haven’t been able to make it, you have no excuse!!!

saturday september 6, 9am (free): i’m leading a walk for nyc queer birders at marine park salt marsh nature center in brooklyn! meet at nature center entrance, no registration required

thursday september 18, 5:30pm (free): prospect park birding with the young convervationists, meet at stranahan monument in prospect park, across from grand army plaza. register here.

sunday september 21, 9am (free): intro to birding at marine park salt marsh nature center. meet at nature center entrance. no registration required.

thursday september 25, 5:30pm (free): prospect park birding with the young convervationists, meet at stranahan monument in prospect park, across from grand army plaza. register here.

friday, september 26, 5pm (free): birding tour of bryant park, meet at bryant park info kiosk by fountain. no registration required.

saturday september 27, 10am (free): signs of fall birds walk @ shirley chisholm state park in brooklyn, meet at fountain avenue entrance. registration required, register here.

sunday, october 12, 9:30am ($17, comes with park admission): fall birding @ wave hill. meet at book shop, tickets here.

saturday october 18, 9am (free): intro to birding at marine park salt marsh nature center. meet at nature center entrance. no registration required.

saturday, october 25, 4:30-8:30pm ($65, $50 for members): nighthunters: an evening owl adventure @ wave hill. this event features a nature walk, a falconry demonstration, and BIRD TRIVIA!!! tickets here.

sunday october 26, 9:30 (free): fall birding in canarsie park with the young conservationists. meet at canarsie park house (seaview ave and e88 st). register here.

—

and now without further ado: a good old-fashioned blog like the ones i was once paid a living wage to write. those were the good ol’ days.

—

i often look at butterflies and think, wow. it’s incredible that the random forces of evolution could have created something so beautiful, so intricately patterned and ornamented. but the truth is, they’re not totally random—any number of pressures from predators, prey, competition within a species, or the environment can lead to some strange traits arising.

and for a significant number of butterfly species, that means having a butt that looks like a head. well, technically a hindwing that looks like a head. but for this post i will be using “hindwing” and “butt” interchangeably for comedic effect.

how exactly does a butt-head come about? that’s what a new paper from researchers at the indian institute of science education and research thiruvananthapuram seeks to uncover. and while the answer is “evolution,” the researchers deem their work the first comprehensive analysis of the pareidolic rear end of the large lycaenidae family of butterflies. this family happens to comprise many butterfly-watcher favorites like the hairstreaks, coppers, and harvesters.

let’s start with a primer on natural selection and evolution. a given population of creatures will demonstrate variability caused by small differences and random genetic mutations. some individuals are larger, while some have bigger legs, or coarser hair, or slightly longer wings, etc. add pressures like finding food, not being food, attracting a mate, or withstanding the elements, and certain differences will prove beneficial and more likely for the next generation to inherit. others will prove less beneficial and less likely to be inherited. some traits might prove neither positive nor negative and be inherited because they’re already there.

evolution is a dynamic force and the driver of speciation. populations separated by distance will adapt to different pressures and eventually accumulate enough differences that they become new species. subgroups of the same population might find different opportunities and diverge as each group adapts to better exploit what’s available, like birds developing smaller or larger beaks to eat smaller or larger prey. every living thing experiences these forces together, and inter-species interactions add further pressures that cause species to evolve together. flowers evolve to accommodate the insects that pollinate them, while peregrine falcons and pigeon undergo a sort of evolutoinary arms race, each growing faster to better catch their prey or escape their predator, respectively.

but i think a major misunderstanding about evolution is that it points someplace. this is not the case—it’s a random walk taken over generations. selective pressures might ping-pong to prefer one trait or another; cyclic prey availability might favor large-billed birds in some years and small-billed birds in other years. an animal adapting to a very specific evolutionary pressure, like hyper-specializing to feed on one kind of food, will go extinct if that food disappears. some traits exist for no reason. long-lasting evolutionary pressures might lead to increasingly complex traits like a head for a butt—but also, there’s no rule saying things have to get more complex over time. the pressures that lead to a butt-head could go away and so, too, would the need to waste energy producing such a complex structure. maybe one day humans will evolve into bugs!

now, for prey, a common selective pressure is not being eaten. sometimes this leads to amazing camouflage, like crickets mimicking leaves or moths patterned like bark. other times it leads to the production of foul-tasting or poisonous chemicals alongside bright colors to signal the creature’s unpalatability. and still other times, it leads to features meant to distract predators.

for many butterflies, distraction features manifest as circles that look like eyes placed far from their vital organs. a predator might go for the eyes and leave with a mouth full of wing scales, allowing for the butterfly to escape mostly intact. in one 1985 study researchers painted various fake head features onto the rears of butterflies without fake heads and fed them to great tits; the tits were more likely to bite the wrong end of the insects with eyespots specifically, and the more complex the fake head, the more likely the bird was to handle the butterfly by the hindwing versus the real head. those with false heads were also more likely to be mishandled by the predators and then escape.

painting a butterfly rear is one thing—the random walk of evolution doing it independently is another. uncovering the evolutionary story leading to a butterfly butt shaped like a head was the goal of researchers tarunkishwor yumnam and ullasa kondandaramaiah.

the pair began by establishing five traits that make up the false head defense. the first, of course, is the eye-like spot. the second, false antennae. the third, a ridge on the wing that looks like the contour of the head. the fourth, bright coloration, and the fifth, lines on the wings that draw predator eyes toward the false head. they analyzed 928 butterfly species, noting which ones had which traits, and used a model to create the most likely evolutionary family trees based on the genomes of these butterflies. they also created statistical models of what these family trees might look like if each of the five traits were correlated (or not) and models to establish the order that these traits arose. they analyzed their trees, capturing how each trait moved along the branches.

the results? well, bright color, fake antennae, eye spots, and the false head contour were all correlated, meaning they generally arose and were inherited together. they also seemed to arise in that order, chronologically. stripes pointing to the fake head weren’t correlated with the other four, meaning that the trait apparently evolved independently. the analysis also revealed that head-butts arose multiple times in the family tree, but didn’t always increase in complexity over time. different selective pressures could cause one or more of the traits to disappear, and head-butts that fooled some predators might not fool others.

of course, this work is based on fancy models, and models can’t reveal everything, nor do they necessarily tell a 100% accurate story about the past. what specific selective pressures, and which predators, promote which of the fake head traits? is deflecting a predator the only thing keeping the trait around, or is the trait also supported by sexual selection and/or other unstudied forces?

and now i get to answer the most important question, which is “why should you care.” well first, this is a great case study on the messiness of evolution. on the surface, complex structures like these might feel like intelligent design. but as the models show, these butterflies aren’t racing to evolve the most beautiful head-butt. rather, there’s a whole spectrum of headbutthood in the family, where some butterflies have heads for butts, some don’t, and different selection pressures lead to differeing appearances of those fake heads—or the loss of them completely.

but honestly you should mostly care because butterfly nerds (me included) will like you better if you’re excited about the butterflies in the lycaenidae family, because it means you’re as nerdy as we are. i don’t make the rules, that’s just how it works.

postscript

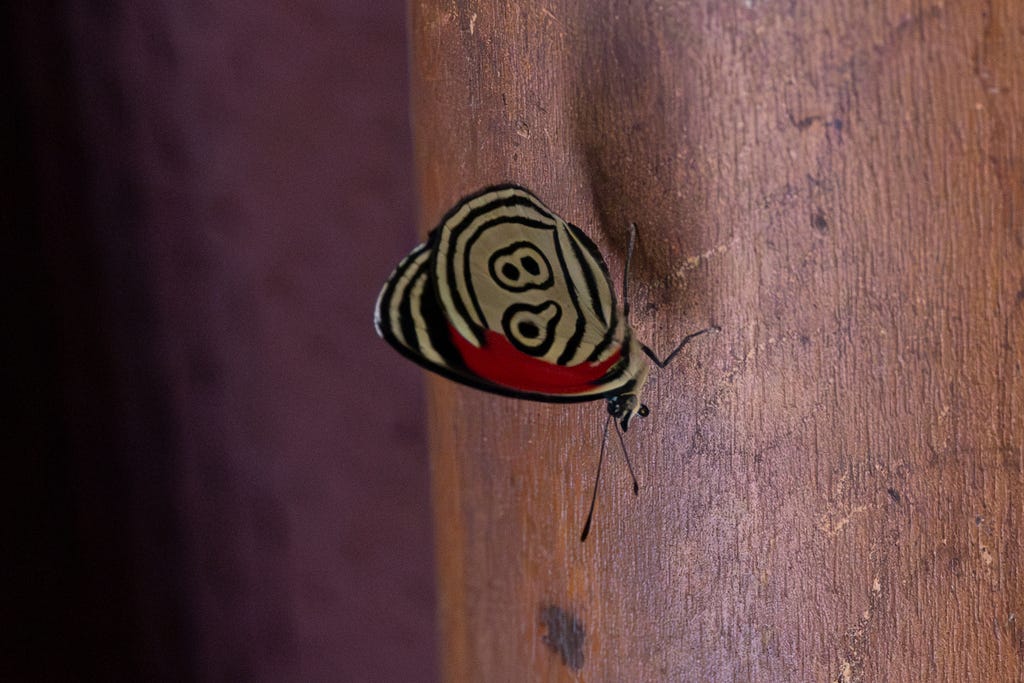

there’s heads-for-butts, and then there’s whatever the hell is going on here—an eighty-eight butterfly (here looking more like a 98) which i saw in colombia earlier this year. nature is amazing.