why is the east's most common animal a new york city rarity?

SALAMANDER SEASON!!!

prescript

for as long as it’s book season (another month or two) the postscript will be a prescript and the posting frequency will be up so i can continue hawking my wares :) as a reminder, you can buy my book here or ask for it wherever books are sold. otherwise, please please come see me at one of these upcoming events! more to come.

#1: pigeon portraits and prose, may 3, 1:30-3:00pm @ caveat on the les. $15, $20 at the door, tickets available here. chelsea and i are hosting an irreverent nature writing and illustration workshop.

#2: intro to birding, may 4, 9-10:30am @ marine park salt marsh nature center. free, no registration required.

#3: golden hour bird walk, may 8, 6-7:30pm @ prospect park stranahan monument. free, registration encouraged.

#4: wings over wave hill, may 18. bird walk 9:30-11am, bird talk on how to document urban wildlife 4:30-5:30pm. all @ wave hill. free with admission to the grounds.

it’s the most wonderful time of year for new york city naturalists: salamander season!!! …or at least, it would be the most wonderful time if it wasn’t also the best time for migrating birds and if there were actually salamanders to look at.

outside of nyc, salamanders likely represent eastern north america’s most abundant animal by mass, thanks to the eastern red-backed salamander. inside nyc, the forces of urbanization have made salamanders a rarity, confined to the city’s outer limits plus a few urban greenspaces. but there are still species hanging on—surprisingly so, in some cases. they become more active and visible in spring as temperatures warm, so i went on a few salamander-viewing trips with friends last month.

to celebrate this exciting time of year, i’m putting together a series of posts about the complex relationship between nyc and these salamanders. the first will explore why a city that supports so much biodiversity can’t manage to host the eastern forest’s most common animal. the second details how the city’s ice age history allows a large, polka-dotted creature to thrive. and the third visits the surprising place in manhattan where a habitat-restricted salamander has held on, against all odds.

but first: what is a salamander and how do you observe them? salamanders are amphibians like frogs but with long bodies and tails that make them look like lizards. they live mostly in the northern hemisphere’s temperate regions. they have a wide diversity of life histories: some begin their lives as aquatic larvae with gills and then mature into terrestrial beings, some spend their whole lives underwater, some spend their whole lives on land, and some—the newts—are born in water, move to the land for a few years, then return to the water.

finding salamanders usually requires searching for shady, moist areas and peering beneath rocks, logs, trash, or other things on the ground. it’s good habit to flip the object toward you—if there’s a snake under the log, you’ll be happy to have the barrier. if you choose to handle salamanders, avoid touching them with bare hands and be very gentle with them. leave no trace on the scene — return the animals and their cover to their initial positions. but none of that matters in prospect park or central park, because there are no salamanders. find out why below.

for a long time, i assumed that the eastern united states’ animals were just the normal ones. we don’t have elephants, polar bears, flamingoes, or other animals that you’d see in nature documentaries that make us unique, i thought. the lowly salamander proved me wrong.

the nearby appalachian mountains are the salamander’s center of diversity, hosting at least 70 of the world’s 550 or so species especially in the southern half of the mountain range. the habitat is perfect with its shady, moist, temperate forests, and the southern appalachians resisted glaciation during the last ice age, allowing them to serve as a refuge for salamanders who could continue filling available niches instead of succumbing to the glaciers. though not as diverse here, new york still supports 18 salamander species.

the abundance is even more shocking than the diversity thanks to the eastern red-backed salamander. red-backed salamanders primarily live underground in forested areas with moist soil, a requirement to stay cool and breathe through their skin since they’re cold-blooded and don’t have lungs. there’s lots of appropriate habitat in our forests, and large-scale studies have found that eastern north america averages around 10,000 red-backed salamanders per hectare (~two american football fields). they might even surpass the total mass of our white-tailed deer.

and yet despite this abundance, eastern red-backed salamanders are missing from many nyc parks, including both prospect park and central park, even though both host forests that would look like fine salamander habitat elsewhere.

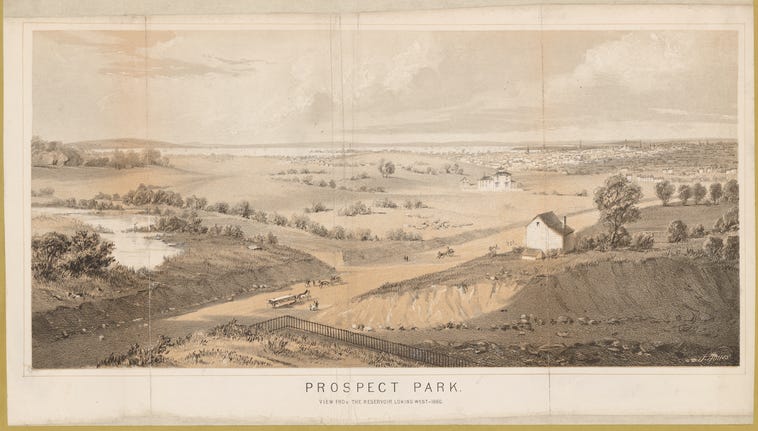

i couldn’t find specific studies about their absence, but i could guess why. you can’t overstate the scale of alteration that nyc’s land has undergone. though the city was once a mega-biodiverse region with forests, marshes, grasslands, and more, old photos of central park and prospect park reveal rolling hills devoid of vegetation, the land cleared, plowed, and tilled for farming and grazing. plus, new york was once significantly more polluted, and a skin-breathing, moisture-needing creature is sensitive to a toxic environment. salamanders may be resilient, but they require clean soil, tree cover, and ground cover like downed trees—which were largely missing from nyc during european colonization

today, some of nyc’s parks simulate the forests outside of the city with artificial waterways and human-planted flora. some species have responded and re-colonized the region in kind. most notably, the city today has far more lichen diversity than it did during the mid-20th century since lichen is very sensitive to air pollution. but paved areas stymie salamander dispersal. so, even after we restore some habitat, there’s no natural way for red-backed salamanders to return.

thankfully, while many of the city’s natural ares are too far-gone to host salamanders, others have preserved them. rocky terrain in uptown manhattan, north queens, and the bronx left areas unsuitable for urban development, in some instances becoming fenced off as part of wealthy estates. you can still find salamanders with regularity in these areas, including inwood hill park, van cortlandt park, forest park, and the staten island greenbelt, though often localized to specific areas.

and then there’s the curious case of brooklyn’s green-wood cemetery. aside from one well-known actress’ yard, for some reason (????) , green-wood hosts brooklyn’s only population of eastern red-backed salamanders. from my understanding, they’re mostly confined to the dell water. dell water is an artificially constructed but natural-feeling part of the cemtery with lots of leaf litter, downed logs, low shrubs, and tall trees on its steep slopes. researchers have recently placed rubber mats specifically for the salamanders.

i have no idea why salamanders persist at green-wood but not at prospect park, which looks far more like salamander habitat. logic tells me that green-wood’s soil wasn’t disturbed intensely enough to eradicate them so they’ve held on, but i don’t know for sure. and they’re not totally safe; studies have found that in urban areas, fragmenting salamander habitats can lead to genetic bottlenecks and loss of diversity which can result in inbreeding and threaten the population.

for the past few years, i’ve been focusing on the fact that cities are wildlife habitat, critical wildlife habitat in some cases. this might leave the reader with a rosy feeling that it’s possible to live harmoniously with wildlife in cities. but our missing red-backed salamanders represent permanent damage done—much of what we’ve lost through urbanization may never return. let it be a reminder, lest we lose something else. and let’s be nice to the salamanders that remain :)