sunday, february 26, 2023 is a day that will go down in new york history: the day that sunset park, brooklyn became the best place to experience the great plains east of illinois.

i’m talking about birds, of course. that day, two birds that share a common habitat in the west showed up less than a mile from each other—both very rare for the city. it’s been exciting for us birders to observe these birds, but it made me wonder whether there’s some bigger natural force afoot.

here’s the tale: on january eighth, birder maureen seaberg spotted a tame hawk on a power line in a parking lot on the staten island waterfront, across the street from an mta subway car repair shop. nothing about the hawk’s behavior indicated anything out-of-the-ordinary—it was perched and eating rats like any of our urban raptors. but its shape and markings felt off, so she sent photos to anthony ciancimino, an experienced birder who’s a volunteer reviewer for the citizen science bird database app, ebird.

anthony immediately recognized the species: maureen had photographed a swainson’s hawk, a migratory raptor of the great plains and western prairies. it was an exceptional find—this bird was thousands of miles north of its expected winter range of argentina’s pampas grasslands. dozens of birders gathered in the parking lot to see it.

the hawk disappeared from staten island, but the next month birder michael silber photographed another swainson’s hawk, probably the same bird, across the water in brooklyn’s green-wood cemetery. the bird reappeared on february 26 when it buzzed the group of green-wood’s bird guide, rob jett, who saw it head westward out of the cemetery. brooklyn birder josh malbin spent hours searching the entire brooklyn waterfront and located the hawk’s new hangout, a recycling plant on the north side of the industry city warehouse complex. it’s remained there since.

during josh’s search, he followed up on a report of a bird from nearby bush terminal piers park: a meadowlark, a grassland-loving songbird whose eastern version is expected in the outer boroughs in the winter. but this meadowlark didn’t feel right for an eastern meadowlark—it was in strange habitat and it looked really pale. some of us went to get closer looks the next day. it cooperated, and revealed itself to be a western meadowlar. eastern meadowlark tail feathers have a thick dark line down the middle with ribs, while western meadowlark tail feathers have horizontal bars.

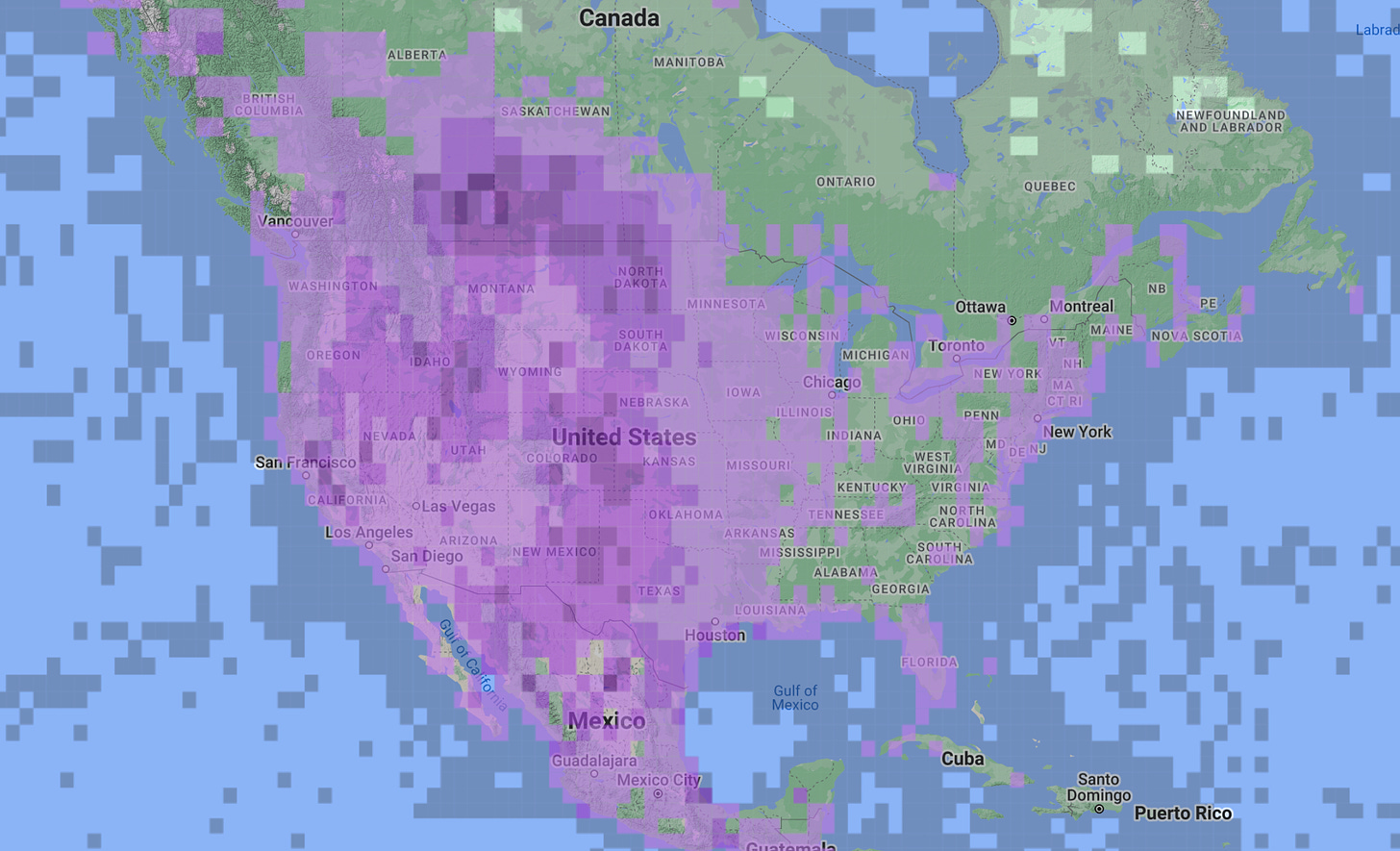

it was the first time either species had been seen in brooklyn. but even stranger was that these two iconic birds of our western prairies, with very similar range maps during breeding season, had ended up in the same patch of un-prairielike habitat at the same time—many miles away from where they should have been.

when you see an avian coincidence like this, it’s hard not to ask why. sometimes there are obvious forces that cause out-of-place birds to show up in the city. in 2015, fast-moving west winds across the united states hurtled many franklin’s gulls to the east coast. cave swallows show up almost annually in the city in response to strong south winds. hurricanes regularly push birds inland. sometimes, several individuals of certain bird species will show up as vagrants in different places at the same time, signaling the potential for some sort of cause—in autumn of 2020, southwestern birds called painted redstarts showed up in new york, minnesota, and north carolina around the same time.

it would be hard to identify a pattern out of just two individual birds. folks with more time than i might start by pulling old records of western meadowlarks and swainson’s hawks appearing in the northeast in the winter and seeing if they’re correlated. maybe they can research whether some natural, unnatural, or supernatural events in the west correlate with what we’re seeing. but correlation isn’t causation, so you’d then need to perform further study to see if the cause produces more vagrants in the future, et cetera.

but getting lost is a thing that birds do. and while it may suck for the lost individual, it can be beneficial for the species overall. hawai’i’s native finches, for example, probably arrived after a group of vagrant finches from asia ended up on the hawai’ian islands. many island bird species throughout the world are the result of vagrancy. cattle egrets are an african, asian, and european species that colonized the americas on their own.

and, while both records are strange, neither are unprecedented. western meadowlarks slowly expanded their range eastward—eventually breeding in new york state during the middle of the 20th century. they haven’t been recorded breeding in any of the state’s breeding bird atlases (meaning, not since 1980), but regularly show up elsewhere as vagrants in the winter. swainson’s hawks are an almost-annual sight during fall migration at cape may, nj, and presumably fly over new york annually, too. winter vagrant swainson’s hawks are much more notable, but again, not totally unprecedented.

migration is beginning, and these birds should soon depart to who-knows-where. maybe they’ll return next winter—some vagrant birds have returned to new york city multiple years in a row. but soon, these birds will just be interesting historical records as more expected and unexpected birds pass through.

postscript:

oof, sorry, i drafted this blog a month ago but have been too busy to edit it. both birds are still present in their spots though so it’s relevant.

i’ll be doing a virtual intro-to-birding for wave hill in the bronx on thursday, april 6 from 4pm to 5:30pm. register here.

finally, i said north dakota, but maybe it’s more like texas. i went to see yet another rare vagrant bird from the gulf coast, a mottled duck, which has been hanging out in a suburban pond in amityville. i went last year and missed it, but i’m glad i was able to go see it this year.